‘Wuthering Heights’ is a Decent Erotic Fan-Fiction and Vastly Poor Adaptation

Courtesy of Warner Bros. Pictures.

Emerald Fennell’s ‘Wuthering Heights’ is an adaptation fashioned less from Emily Brontë’s 1847 novel than from the memory of encountering it in adolescence. The 2026 film treats Brontë’s work as a set of aesthetic cues and erotic gestures rather than an unsettling look at classism, race, and patriarchal societies that the original text had, which elevated English literature.

The project frames itself as interpretation rather than translation. The title is hedged with quotation marks; the director’s commentary foregrounds personal response over literary engagement. The result is a film that mistakes emotional extremity for mood, and violence for ornament. Brontë’s novel (an exercise in psychic brutality so intense that early critics deemed it morally corrupting) is here rendered into something purely decorative. Whatever else it may be, this is not a work that challenges the reader, or in this case the viewer, with discomfort.

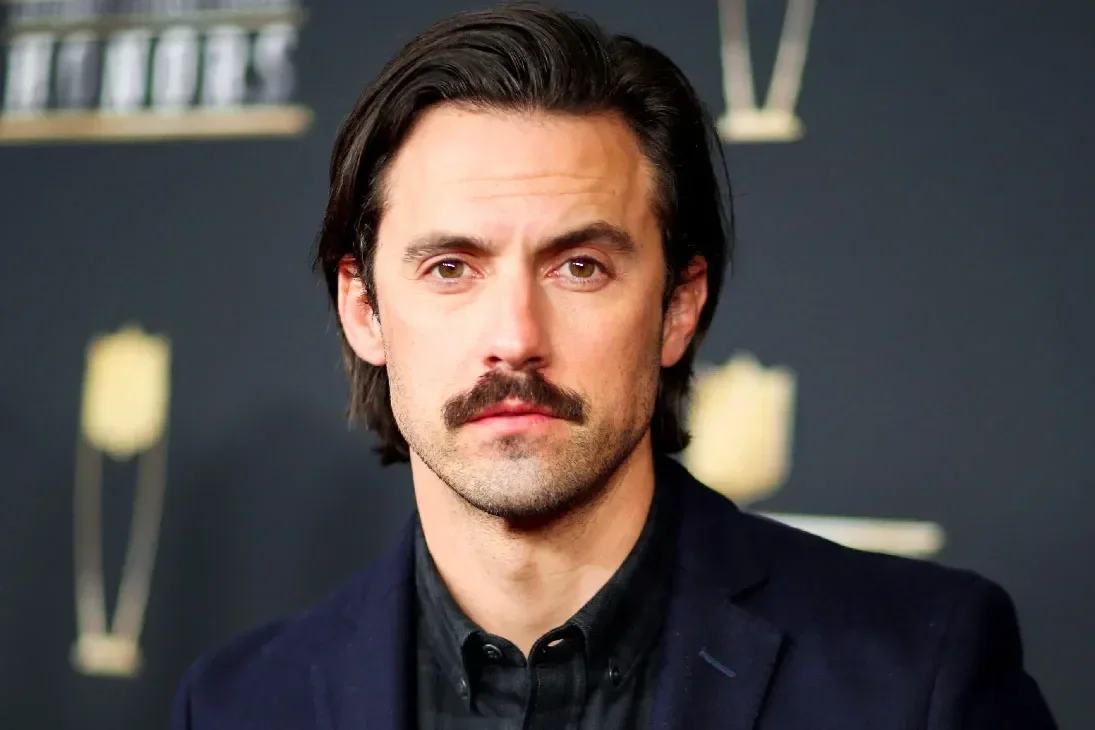

That softening is evident most immediately in the film’s casting and its narrative omissions. Heathcliff, whose racialized otherness is a source of sustained anxiety and cruelty in the novel, is played by Jacob Elordi, a choice that quietly erases the book’s preoccupation with alienation, classed and racialised violence, and social exclusion. Cathy, embodied by Margot Robbie in luminous blonde-and-blue-eyed splendour, becomes less the contradictory, socially anxious figure of the text than an already-legible romantic heroine. The Lintons (symbols in the novel of pallid respectability and aspirational gentility) fade into near irrelevance.

Fennell appears uninterested in the tensions that animate Brontë’s story: not only the erotic charge between Cathy and Heathcliff, but the way that charge is corroded by resentment, humiliation, and an appetite for domination. The novel’s emotional engine is a naked, self-consuming rage. By contrast, this adaptation is timid, even when measured against Fennell’s own filmography, which has previously demonstrated a keen eye for self-loathing and moral collapse. There is more of Brontë’s ferocity in the characters of ‘Promising Young Woman’ or ‘Saltburn’ than in this film’s Heathcliff and Cathy.

The adaptation confines itself to the novel’s first half, a decision with a long cinematic pedigree and, in itself, no great sin. The issue is not fidelity but temperament. Heathcliff, stripped of his vindictiveness, becomes a melancholy romantic cipher (perpetually damp, perpetually devoted, and never meaningfully dangerous). The abused child who grows into a man so consumed by revenge that he replicates the cruelty he suffered is replaced by a figure engineered for swooning rather than reckoning.

This dilution is compounded by a key narrative decision: the conflation of Hindley Earnshaw with Cathy’s father, transforming the latter into a brute who abuses both children equally. In flattening these relationships, the film reduces Brontë’s morally perverse architecture to a familiar romance plot. Cathy becomes the impoverished girl who marries security while yearning for passion; Heathcliff the penniless soulmate who departs only to return, improbably wealthy, as if having undergone a romcom makeover rather than a ruthless campaign of self-enrichment designed to destroy his enemies.

Visually, the film commits fully to this romanticisation. The costumes and sets gesture toward mid-century fairy-tale cinema, filtered through a cinematography so soft it threatens to dissolve the moors into gauze. Yet when set against Brontë’s language of abrasive, elemental, resistant to prettification, these flourishes feel less evocative than incongruous, their lushness recalling the hollow spectacle of live-action fantasy rather than Gothic severity. Only the musical score, with its undercurrent of dread, gestures toward the menace the film otherwise avoids.

Fennell has described the film as a “sadomasochistic” provocation, but here, too, the execution is peculiarly toothless. Transgressive images are introduced only to be defanged by irony, played broadly for shock or laughter. Class difference is fetishised rather than interrogated: the poor are framed as licentious and animalistic, the rich as baffled innocents. Desire, instead of destabilising the social order, becomes another visual flourish.

Even the central relationship, so infamous for its cruelty, is rendered decorous. Heathcliff’s “wildness” rarely exceeds the eroticism of a Sunday-night costume drama. Robbie and Elordi share a serviceable chemistry, but their characters are so aggressively simplified that performance shades toward caricature. She is spiky and impulsive; he is rough yet tender. The essentials that make Brontë’s work unforgettable are utterly absent.

A truly faithful ‘Wuthering Heights’ adaptation (faithful to story and themes) would be profoundly unmarketable. It would repel as much as it enthralled. It would not lend itself to tie-in campaigns or Valentine’s Day screenings. If Fennell’s film fails to capture what it feels like to read Brontë, that failure only sharpens the novel’s continued singularity.

Brontë emerges, once again, dominate and unassimilable.

‘Wuthering Heights’ score: ★☆☆☆☆